Words and wellbeing

Shaping a better reality through language

This article was originally posted on Medium on December 12, 2024.

Hi, I’m Megan. I’m a Principal Content Designer at Vimeo by day. By night and weekend, I’m pursuing a Masters in Happiness Studies. In my work as a Content Designer, I spend a lot of time thinking about words — and in my studies I’ve learned that words can actually make a pretty big difference in our happiness, too.

That’s what this article is about: words, wellbeing, and how we can all shape a better reality through language. I’ll cover:

- The impact of words in digital products

- Why the words we choose matter

- Word related challenges that get in the way of happiness

- The power of words in making a difference

- Tips for shaping a better reality through language

The impact of words in digital products

Before we get into shaping reality, let’s take a quick look at how words can shape our experience on a smaller level—in digital products. Are you ready?

…Are you sure you’re ready?

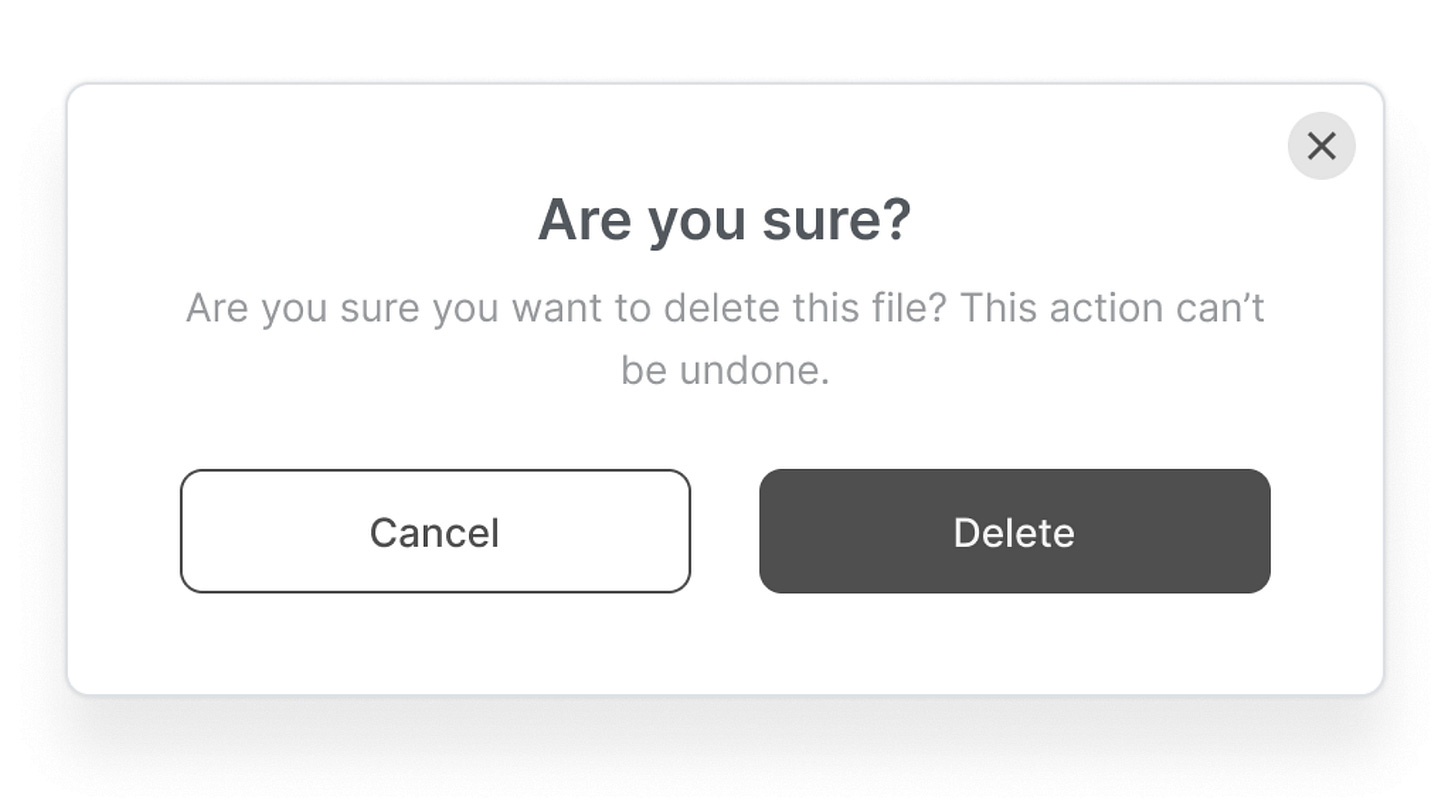

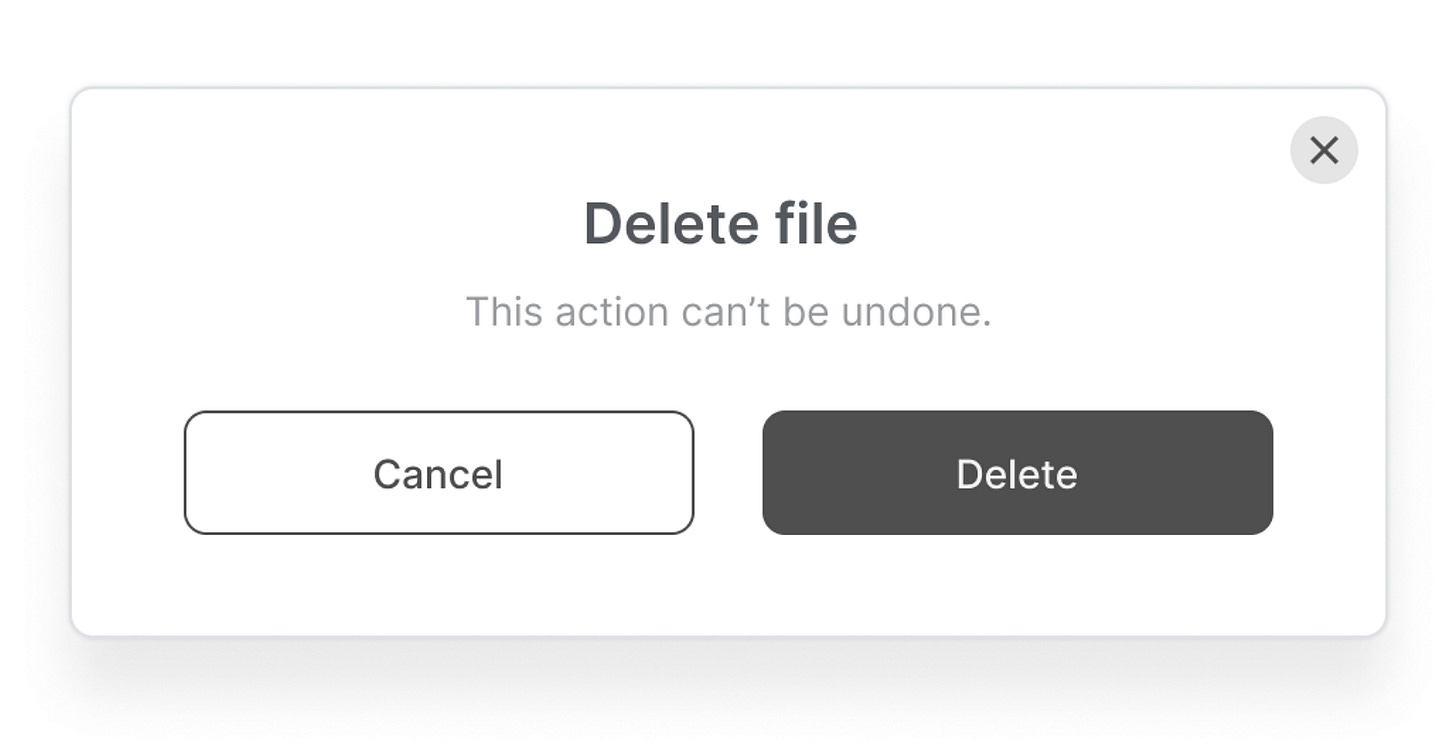

This is a confirmation modal. Its purpose is to add just a little bit of friction to an experience to prevent someone from accidentally doing something they can’t undo, like deleting a file. It’s pretty common for modals like this to ask “Are you sure?” But subconsciously — or even consciously — that question can feel kinda bad. If you’re trying to do something, and I ask “Are you sure you want to do that?” it’s not fun. It undermines your confidence. It’s patronizing.

By changing “Are you sure?” to “Delete file” we serve the same purpose without the bad feelings. You click “Delete” and move on with your day.

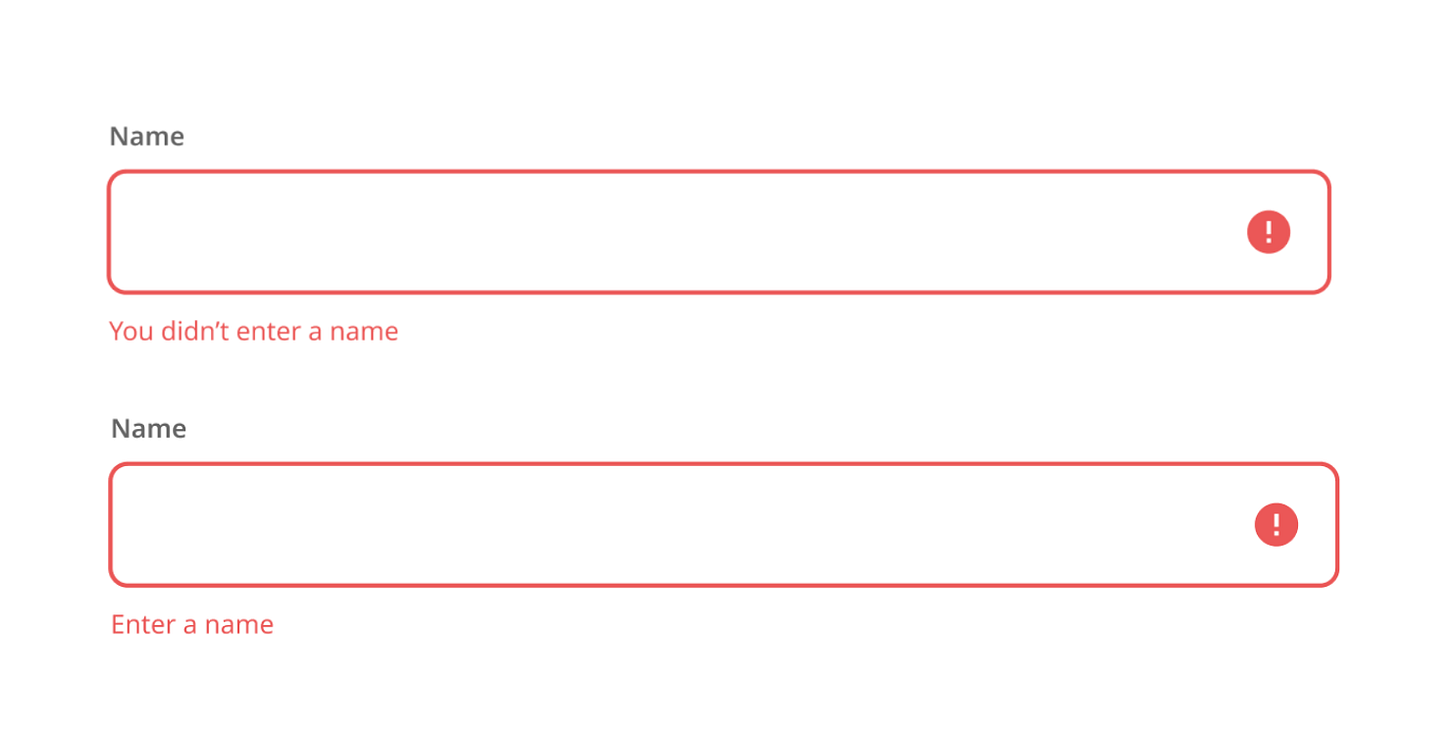

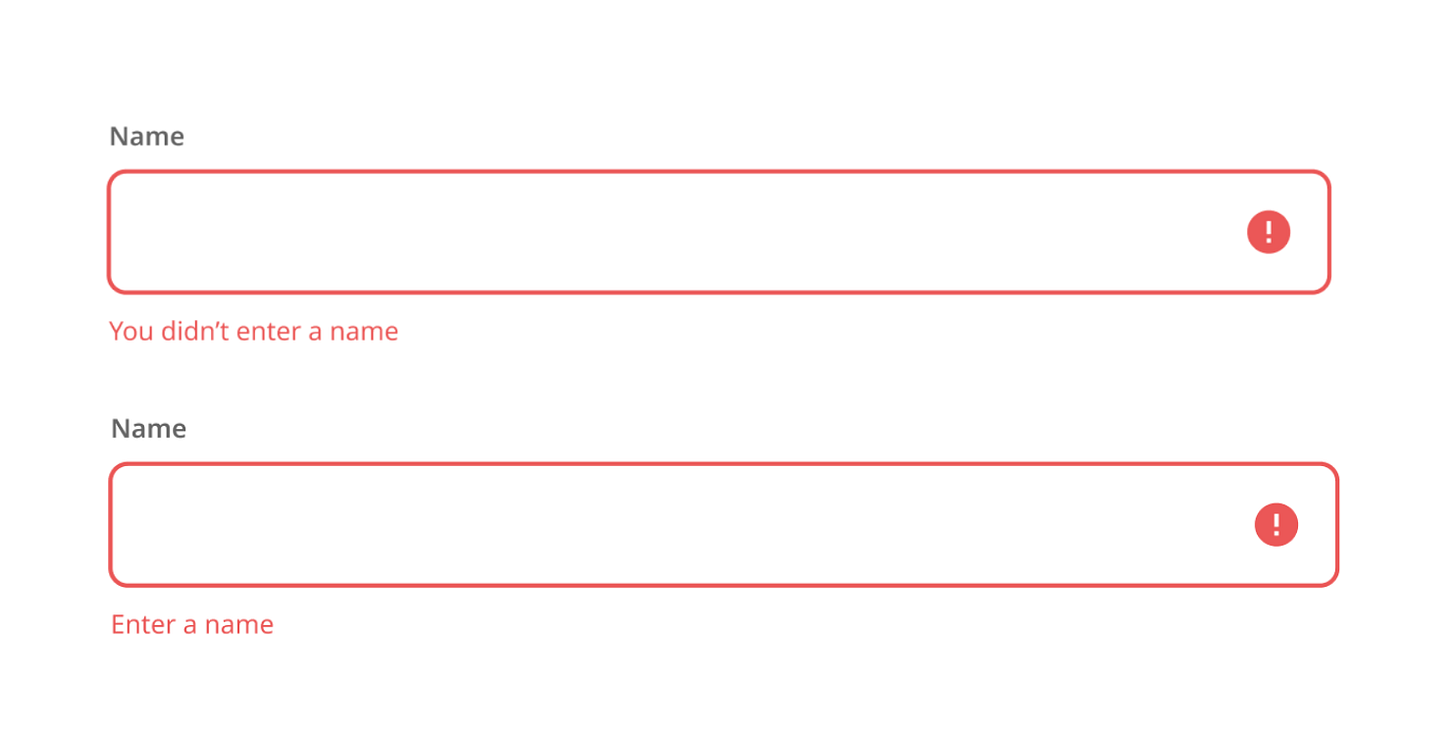

Here’s another example. “You didn’t enter your name” places blame on the user. “Enter a name” reframes the message to let the user know what they need to do to proceed without placing blame.

If something as simple as rephrasing an error message can reduce frustration, imagine what rephrasing how we talk to ourselves and others could do for our lives! By taking the time to use words mindfully, we can improve our mood, our relationships, and make a positive impact on the world around us.

The words we choose matter

Austrian Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued that the words we choose give meaning to the world around us. In his book, Philosophical Investigations, he described a triangle to illustrate this argument:

“This triangle can be seen as a triangular hole,” he wrote… “As a solid, as a geometrical drawing, as standing on its base, as hanging from its apex, as a mountain, as a wedge, as an arrow or pointer, as an overturned object, which is meant to stand on the shorter side of the right angle, as a half parallelogram, and as various other things.”

This doesn’t just apply to triangles, but to people too.

In her article, Interpersonal Mindlessness and Language, Ellen Langer discusses the role language plays in shaping our perceptions. She says, “We typically speak from a single perspective without cognizance of alternative perspectives, ignoring the richness of our language which makes available multiple ways of saying the same thing.”

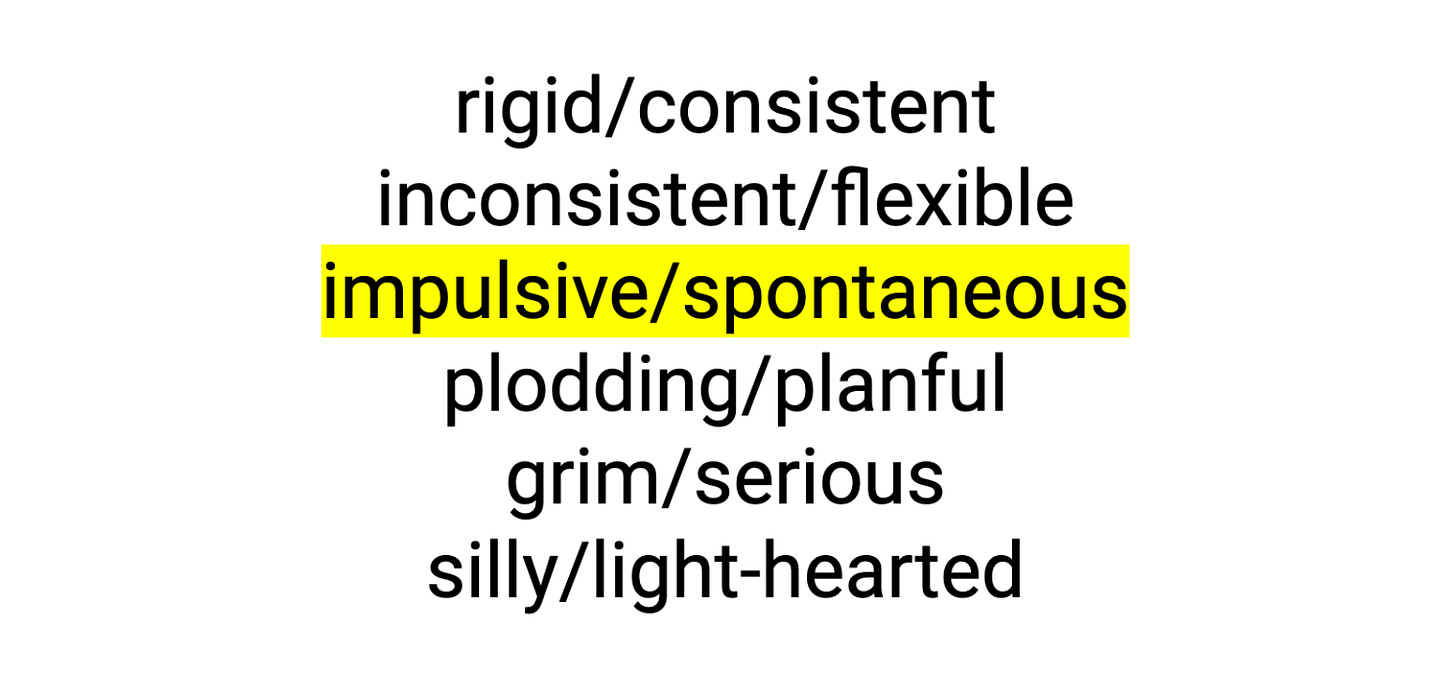

She shares the following list of synonyms. Each of these pairs share similar meaning, but one of the words is more flattering and the other more insulting:

Let’s say you like to do unplanned things. I could decide to call you either “impulsive” or “spontaneous” and the mere choice of that word would color my own and others’ perception of you.

Langer points out that, “It is not a new finding that labels lead to mindless perception of that which is being labelled.” For this reason, it’s important that we take a mindful approach to the words we choose when describing others.

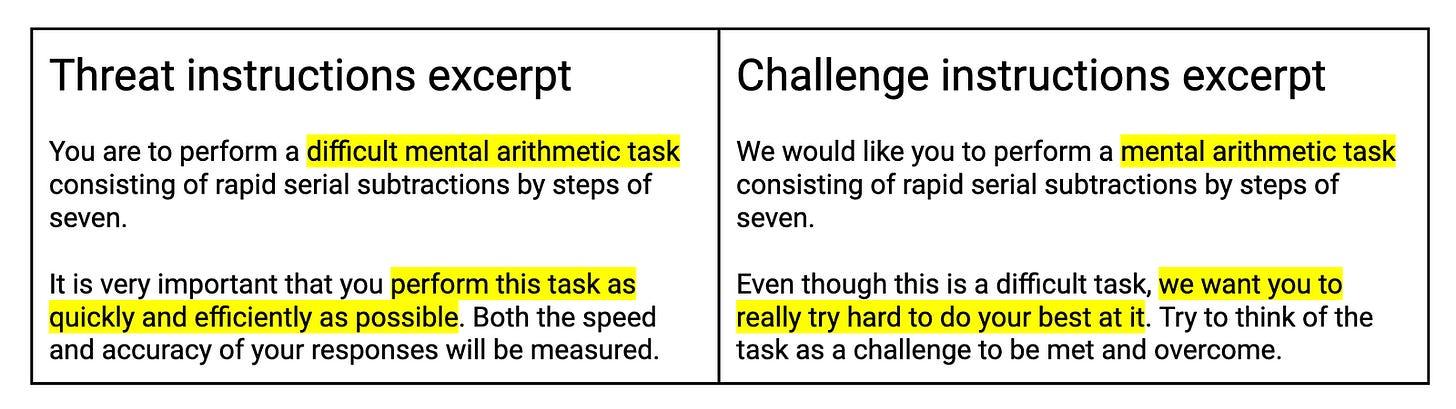

Words can also shape our experiences. A study conducted by Joe Tomaka at New Mexico State University illustrates this. In the study, two groups of participants were given the same mental arithmetic task with slightly different instructions. One set of instructions used language that positioned the task as a threat and the other set used language that positioned the task as a challenge.

The instructions that positioned the task as a threat called out that it was a “difficult mental arithmetic task” and that the participants would need to perform the task “as quickly and efficiently as possible.” The instructions that positioned the task as a challenge used more encouraging language, calling out that “even though this is a difficult task, we want you to really try hard and do your best at it.”

While the groups performed similarly on the task, their experience was very different. Those that saw the test as a challenge were calmer, better able to focus. Those who saw it as a threat experienced stress-related reactions and higher levels of tension. All because of the words that were used to frame the test.

We’ve seen how word choice can change things for the better or worse. From something as simple as an error message, to labeling a person as spontaneous or impulsive, to impacting levels of stress during a test. Why don’t we just use feel-good words all the time, then?

Word-related challenges

The truth of the matter is, it’s easier said than done. Words are hard and there are a lot of word-related challenges standing in our way.

The meaning of words

The first challenge is figuring out the meaning of life! Ah wait, sorry, I meant words. Figuring out the meaning of words!

I think it’s pretty telling that the word “meaning” — the word we use for what is meant by the words we use — has several meanings itself. And “meaning” isn’t the only word with lots of meanings.

Big words central to the theme of wellbeing also mean different things to different people. Words like fun and happiness.

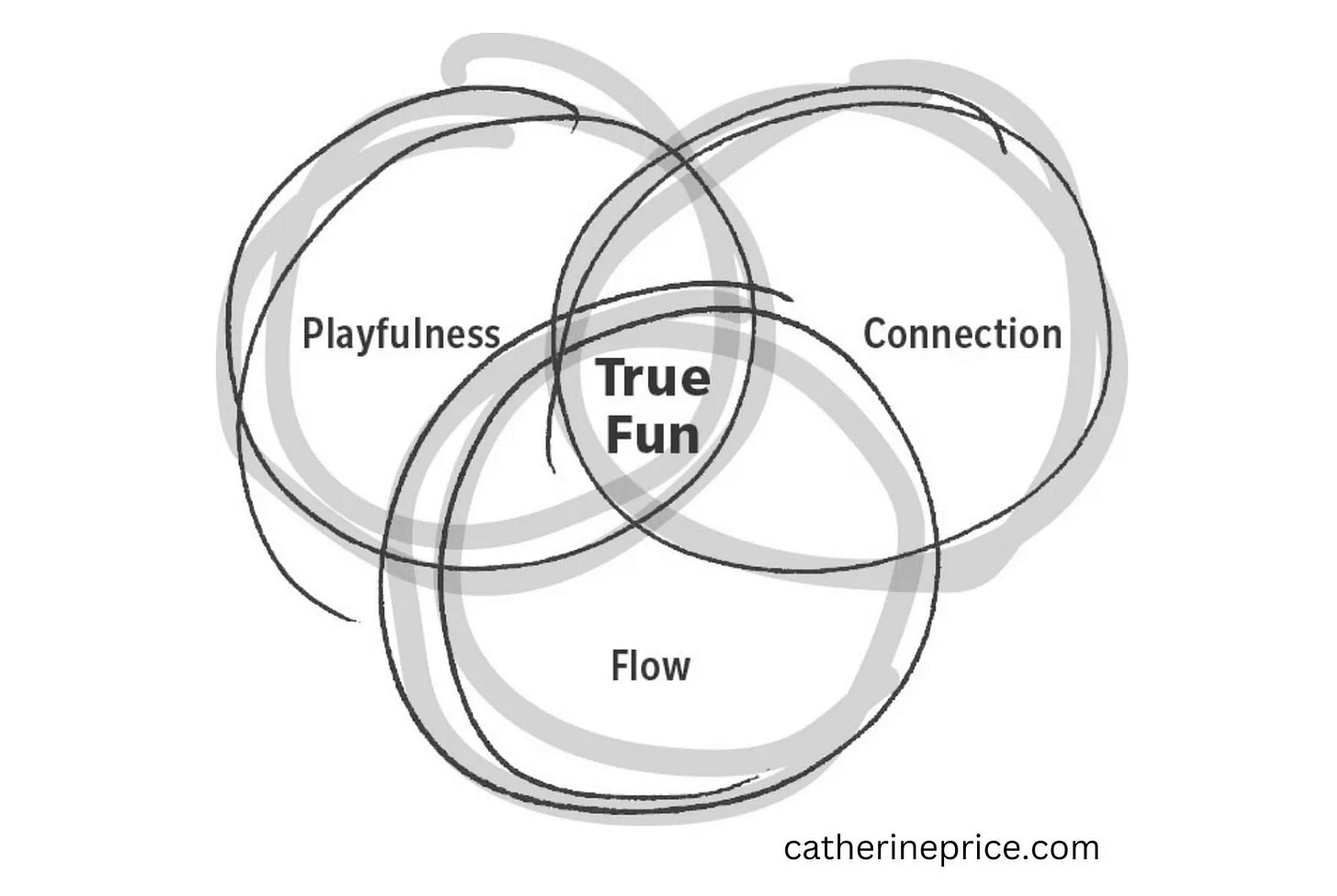

In her book The Power of Fun, Catherine Price says, “Nailing down a definition of fun is surprisingly difficult to do.”

Fun can be any mix of enjoyment or light-hearted pleasure. You can poke fun at people, do things all in good fun, have fun at an amusement park or at jury duty (I hope! I have jury duty coming up soon).

The way we throw the word “fun” around makes it hard for us to really identify when we are having true fun, which Price defines as the confluence of playfulness, connection, and flow. (Probably not something I’m going to experience at jury duty.)

We use the word happiness in a similarly haphazard way.

In his book Happier, Tal Ben-Shahar touches on the difficulty in defining happiness. He says, “Words like pleasure, bliss, ecstasy, and contentment are often used interchangeably with the word happiness, but none of them describes precisely what I mean when I think about happiness.”

To complicate matters even further, the word “happiness” has different connotations across different cultures. In a 2018 study, researchers asked Korean and American participants “What three words come to mind in association with “happiness”? The most-listed word in Korea was “family” while the most popular among Americans was “smile.”

You can imagine that understanding ourselves and each other can be difficult when we don’t have a shared understanding of what these meaningful words even mean.

Limited vocabulary

Outside of shared definitions, most of us have a pretty limited vocabulary when it comes to expressing our emotions. In the quote about happiness, Tal Ben-Shahar shared a few of the words we often use interchangeably with “happiness” — pleasure, bliss, ecstasy, and contentment.

There are countless words we can use to describe how we feel, but most of us stick to a few basic emotions. We feel happy or sad or angry or scared. And we might not even differentiate to this extent. Sometimes we just feel good or bad.

Aside from emotional vocabulary, our vocabulary in general is limited. It’s hard to express ourselves when we don’t have the words.

And using the wrong words can have… not so ideal consequences.

Sorry about that. I just really wanted an excuse to share that clip before getting into the last challenge…

Mindless use of language

…which is the fact that many of us just don’t really think about the words we use — which inevitably leads to misunderstanding.

Ellen Langer says, (referencing philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine), “According to Quine, the greatest problem between people is the uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. I concur, and believe that this popular misunderstanding is largely a function of the mindless use of language.”

The power of words

The good news? Words are powerful tools. And when we use words more intentionally, we can improve our mood, strengthen our relationships, and contribute positively to the world around us.

I love this quote from lexicographer Erin McKean’s TED Talk, The Joy of Lexicography: “Words are the tools that we use to build the expressions of our thoughts.” It follows, then, that by building on the collection of words in our toolkits, we’ll be better able to express our thoughts.

Emotional granularity

Let’s start with emotion words. Some of us are much better at expressing our emotions than others. A 2015 study on Unpacking Emotion Differentiation by Todd Kashdan, Lisa Feldman Barrett, and Patrick E. McKnight, sheds light on this phenomenon.

In the study, they illustrate the concept of emotional differentiation or emotional granularity, or the ability to “[put] feelings into words with a high degree of complexity,” with two quotes from different individuals about how they felt on September 11.

One person said, “My first reaction was this terrible sadness… But the second reaction was that of anger, because you can’t do anything with the sadness.”

The second person said, “I felt a bunch of things I couldn’t put my finger on. Maybe anger, confusion, fear. I just felt bad on September 11th. Really bad.”

Do you identify more with the first person or the second person? I identify with the second person. I struggle with putting my feelings into words.

Well it turns out that “individuals who experience their emotions with more granularity are less likely to resort to… binge drinking, aggression, and self-injurious behavior; show less neural reactivity to rejection; and experience less severe anxiety and depression.”

Luckily hope is not lost for those of us that struggle in this department. Interventions designed to improve emotion differentiation have been shown to increase wellbeing. For example, according to the study, people afraid of spiders experienced less anxiety when trained to differentiate emotions: “In front of me is an ugly spider and it is disgusting, nerve-racking, and yet intriguing.”

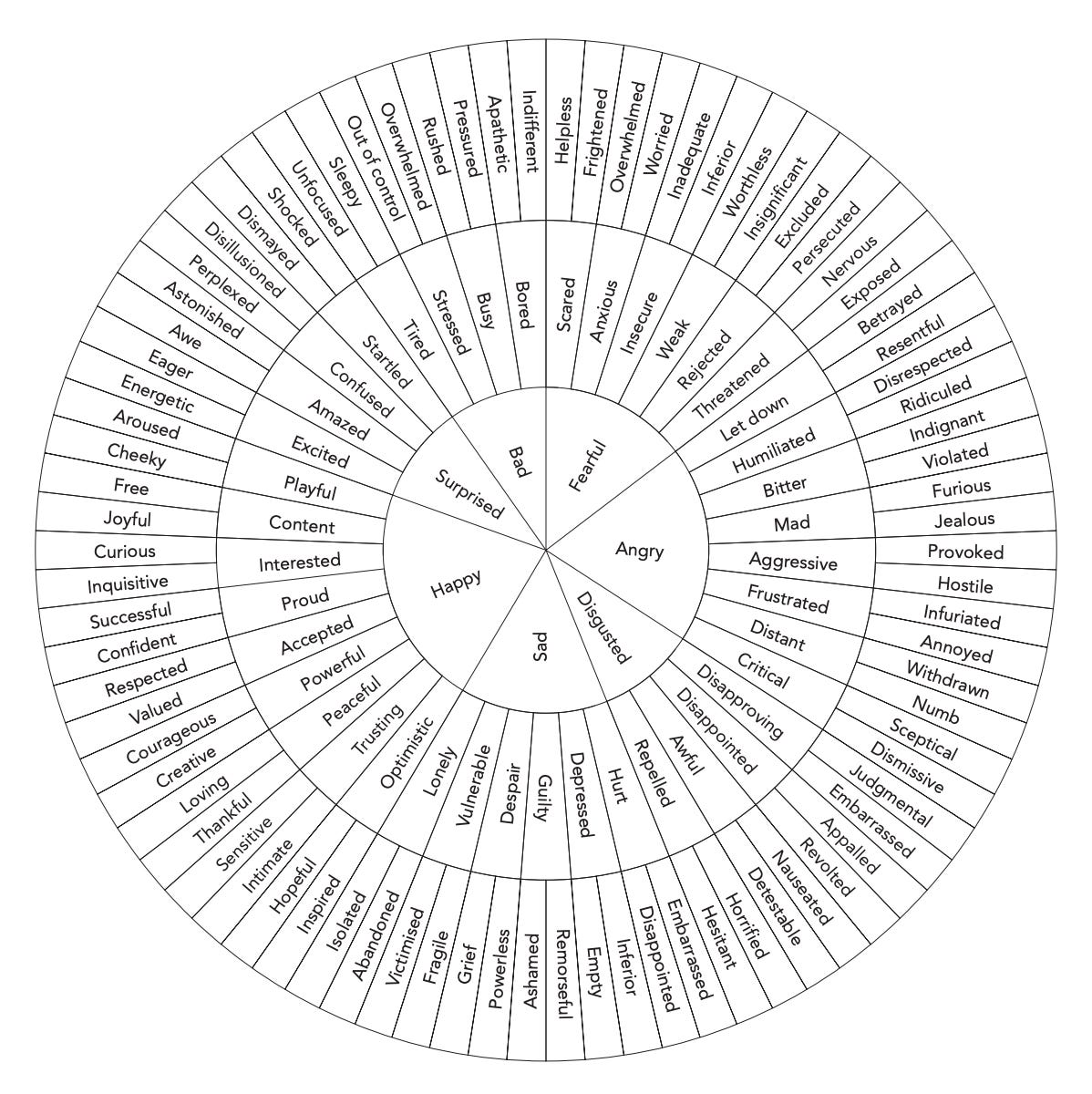

And we can all improve our emotion differentiation by simply becoming more familiar with emotion words. A Feelings Wheel is a good place to start. It breaks down basic emotions into more complex ones. The team at Calm describes the Feelings Wheel on the Calm blog as “a tool that allows individuals to better navigate their inner emotional landscapes and foster healthier emotional intelligence.”

Adding these words to your toolkit and spending time contemplating — or even journaling — about how different situations make you feel can help you improve your emotion differentiation skills. The next time you feel “happy” ask yourself, “How do I feel happy?”

Untranslatable words

Expanding our emotional vocabulary can help, but sometimes there actually just isn’t a word for what we’re trying to express.

In his book, Happiness Found in Translation, Tim Lomas writes, “English does not provide labels that perfectly suit every nuanced feeling… It’s an odd, uncanny event. Without being able to label the experience, we may struggle to register it at all, and certainly to understand and articulate it.”

Sometimes these words do exist in other languages, though. And Lomas suggests that spending time with these untranslatable words can have the same positive effects on wellbeing as broadening our emotional lexicon.

To this end, he launched the Positive Lexicography Project — a collection of untranslatable words related to wellbeing. Lomas’ project contains words like wabi-sabi, a Japanese word for imperfect and aged beauty; ubuntu, a Zulu word for universal kindness and benevolence; and my personal favorite, hyppytyynytyydytys, a Finnish word for the feeling of sinking into a soft chair (which according to Reddit isn’t actually commonly used in Finland, but I still love that this word exists).

Erin McKean also suggests making up your own words! She says, “You should make words because every word is a chance to express your idea and get your meaning across — and new words grab people’s attention.” Here’s another plug for her TED Talk.

English professor Anne Curzan, in another super TED talk on What makes a word real? says made up words like hangry and adorkable “fill important gaps in the English language.”

But whether we have a word for something or not, I think George Orwell says it best in his essay on Politics and the English Language when he says, “What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can.”

Where to start

If you want to start getting your meaning as clear as you can, here are some places to start:

Be mindful of framing

First, be mindful of framing. We’ve seen how the words we choose to describe people can color our and other’s perspectives. And remember our example of the error message, framed first to blame the user and next to simply let the user know what they need to do to proceed?

Framing can have a big impact on blame and punishment, even when something is an accident. In a study on the role of language in constructing agency, Americans were more likely to use agentive language when watching a video of someone breaking a vase accidentally — “She broke the vase” — than Japanese speakers, who were more likely to say “The vase broke.” When framed as “The vase broke,” participants were also less likely to remember who broke the vase later on, making them less likely to place blame.

Similar to the impact we saw in the experiment that framed a task as a challenge or threat, you can gain benefits from reframing difficult events in your life. In course materials, Tal Ben-Shahar (who also happens to be the director of my masters program) recommended taking the time to reframe a difficult situation as challenging, as an opportunity, or any other way in writing and reading it when you need a boost.

Use inclusive language

Using inclusive language can also have a positive impact on those around you. A study on Exposure to Inclusive Language and Well-Being at Work Among Transgender Employees in Australia, conducted in 2020, showed a strong correlation between inclusive language and trans employee wellbeing.

A few places to start include:

- Using gender-neutral terms: Instead of “guys,” try “everyone” or “friends” or “team”

- Using person-first language: Instead of labeling someone as “a homeless person,” you can refer to them as “a person without housing”

- Using plain language: Avoid acronyms, jargon, and metaphors that everyone might not be familiar with

- Not making assumptions: Don’t assume everyone shares your knowledge and experience; avoid saying something’s “easy” that may not actually be easy for everyone

Want to learn more? Check out these resources:

- 18F Content Guide: Inclusive language

- APA Inclusive Language Guide

- Atlassian Design System: Inclusive language

Spend time with words

And last but not least, you can start finding meaning — and increase your levels of happiness — by simply spending more time with words.

We already took a look at how spending time with words can help improve emotion differentiation, and just how much fun untranslatable words can be.

Eknath Easwaran, a spiritual teacher from India, encouraged meditation on words, quotes, and passages, teaching that “We become what we meditate on.” Spending time with wise words that inspire us can have tremendous benefits.

For example, spending time with this Ralph Waldo Emerson quote has made a huge difference in my attitude toward my own artistic endeavors:

And speaking of quotes… I’ll leave you again with this quote from George Orwell:

“What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can.”